SUPER BOWL XXI : DENVER vs. NEW YORK : NFL VETERANS : LIVING WITH THE PAIN : One-Time Ironmen Like Jim Otto, Who Is 49 Going on 90, and Butkus Are Hobbled for Life

SAN DIEGO — He has undergone 18 operations, a dozen of them on his knees. Three times, he has had an artificial knee implanted in his right leg, and he needs a new one. There are fused vertebrae in his back that will require more surgery. He has had his nose fixed to help him breathe more easily, but now his neck needs surgical repair.

Jim Otto belongs in a rocking chair, if not a wheelchair. But as one of the enduring symbols of pro football’s iron-man ethic, he is too proud to be seen in public with so much as a cane.

“I’ve been sore as the dickens every day since I retired 11 years ago,” he said. “Every day is like the day after a game used to be.

“I don’t take any pain medication because I don’t want to get hooked on it. I have learned to live with the pain and I don’t think of living any other way.”

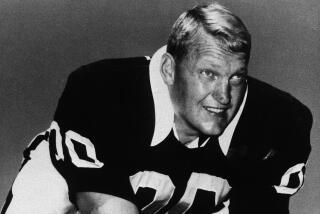

Otto, 49, who for 15 years wore the famed double-zero on his Raider jersey, ranks near the top of the list of most-battered National Football League retirees.

One of seven former players seeking increased benefits for total disability under the league pension plan, he hopes to raise the awareness of the needs of yesterday’s heroes. Some apparently are ignorant of their rights to collect, and others are too embarrassed to come forward and admit how much they hurt.

There are few, though, among the 3,000 or so retired veterans vested in the league’s pension plan who aren’t hurting or hobbled.

“We are talking about trampled gladiators,” said Miki Yaras, director of benefits for the NFL Players Assn. “I deal with the underbelly of the sport. I can rattle off the details of Otto’s knees faster than my own social security number.

“I would guess that at least 70% of retired players can’t put their feet on the floor in the morning without pain. It could be 95%. I would welcome someone to prove me wrong.”

They vary in degree of suffering, from Darryl Stingley, paralyzed for life, to Alan Page, who has a crooked little finger but suffers more anguish from three years as a lawyer representing players frustrated in the attempt to collect better benefits.

In a recent series of interviews with retired players, a common thread emerged. All were affected to some extent by pain and degenerating bodies, a product of the drive that had made them successful players. Some were bitter, but none were anti-football.

Many once believed, naively, that they were indestructible. They responded both to peer pressure and their own internal pressure to play when hurt. In the process, they irreparably damaged the physiques that set them apart from the rest of us. In the main, they accept that as the price of engaging in a collision sport.

A few case studies:

--E.J. Holub, former Kansas City Chief linebacker, has had 17 operations, 12 of them on his knees, but manages to go about his business as a rancher.

“I walk stiff-legged, like Chester on ‘Gunsmoke,’ ” the 49-year-old Holub said. “But I’m still able to drive tractors and bulldozers, ride bucking broncos and cut horses. I’m most affected when I’m unloading hay or pipe, which makes the bones rub on each other.

“I have no regrets. I played in the first and fourth Super Bowls, and I got indescribable pleasure from the companionship of my teammates. To me, the sad part is the steel workers, longshoremen and carpenters, all the men who have injuries but don’t get the ink because they are not gladiators.”

--Stingley, 35, a former New England Patriot wide receiver, is confined to a wheelchair nearly nine years after he was injured in a collision with Raider defensive back Jack Tatum.

“I haven’t given up on life,” said Stingley, who lives in a custom-designed condominium in Chicago and works with organizations that help the handicapped. “I’m not rich, but I’m getting by. I guess I live a middle-class life, but I wish it was upper class.

“My (two) kids are fed and clothed, and there will be enough for their education. If I had played longer and earned more, I would have been able to help more of my family. But I’m not really bitter. From the first bloody lip you get as a kid, you have to assume the risk in this game.”

--Dick Butkus, 44, the former Chicago Bear linebacker, plans to pursue his acting career until the day arrives that he must have an artificial knee.

“There’s a price attached to everything,” said the man once regarded as the most macho figure in the sport. “When I talk about injuries with my pals, I just laugh. I wouldn’t change a damn thing about my career.

“My knee sometimes suckers me into feeling I’m OK, and then stiffens up, but I’ve gone 10 years without surgery. I’ve adjusted my gait to avoid pain, and I just get on with it.

“I can understand why some guys more messed up than me might have bitterness, but not me. I have no qualms, no problem with the game.”

--Charlie Waters, 38, a former Cowboy defensive back, is now in the real estate business. He has an unstable knee that keeps him from running as much as he’d like, but he doesn’t regret the gung-ho attitude he once had.

“I’d go through it all again,” he said. “Nobody but me made me play hurt. I was going to be out there every week and be counted on, by God. Consequently, I am paying for that now.

“I feel fortunate I can walk. Bodies are just not made to put up with what we ask them to do. Future civilizations will look back and say what a bunch of idiots we were.

“But, please stress I am not anti-football. The inner truth is that I made all the decisions as a player. The ones who are bitter aren’t being honest with themselves.”

--Bob Babich, 39, a former San Diego Charger linebacker, is now a banker who works out four times a week to stay in shape. Because of injured knees, he can’t run or play court sports.

“I have arthritis all over my body, but it hasn’t affected my outlook,” he said. “I knew what the consequences of being a football player would be. I am concerned about the aging process. I know the aches and pains will be there. As a player, I was like everyone else. You think you will never get old.”

Some of the wounded can laugh about their pain.

Walt Garrison, a former Cowboy running back, is going into the hospital next month for knee surgery.

“Funny you should ask,” he said. “This is my virgin knee, the one I hurt roping cattle in a rodeo. I can damn near predict the weather from the way my bones feel.”

Garrison, 42, isn’t alarmed by the upsurge in pro football injuries variously attributed to artificial turf, and muscles artificially enlarged through the use of steroids.

“Maybe I was naive, but I never heard of steroids or marijuana,” he said. “Shoot, I never thought injuries would catch me. I thought I’d last till I was 60.

“Let’s face it, this is a contact sport. If you plant your leg, something has to give, and it usually ain’t your helmet or your shoulder pads. . . . I never thought AstroTurf was a big deal, but maybe I just didn’t run fast enough to get something like turf toe.”

Larry Wilson, the former St. Louis Cardinal defensive back who once intercepted two passes in a game while playing with two broken hands, thinks that poor tackling technique is to blame for many injuries in today’s game.

Like Garrison, he makes light of his injuries.

“The only part of me that doesn’t work well is the middle finger on my right hand,” he said. “What that does is just straighten out my golf grip.”

Wilson, 48, had most of his teeth knocked out when he was bounced on his chin while wearing a helmet with a single-bar face mask, but he defended his tackling form.

“We knew how to use our gear to tackle without getting hurt,” he said. “Today, they call some of these folks hitters, but their form isn’t real good. They use their head too much, which results in injuries.”

The rise in injuries can be traced in part to an increase in overly aggressive players, according to Stingley, who is fearful of the consequences of such a trend.

“It’s almost as if nobody paid attention to what happened to me,” he said. “There have been two generations of college kids since I was hurt. I was in the Patriots’ locker room a few years ago, and it was like I was looking at total strangers. They looked at me as if wondering, ‘Is that really him?’

“I would hate to think somebody else would have to go through what I did. About all I can do is keep myself healthy enough to be seen and heard, and be courageous enough to say something.

“It would be worthwhile if I could keep just one guy from inflicting a life-threatening blow on another living, breathing human being. I would like these guys today to realize you don’t become All-Pro by playing dirty.”

Stingley said he felt fortunate in the sense that his case was so publicized that football had to take care of him. Others are less fortunate. Their careers did not end with one sudden, vicious hit that received wide attention.

Roger Stillwell is another of the seven retirees seeking increased disability benefits for a degenerative condition said to be football-related. An arbitrator is expected to rule within a month on the cases of Stillwell, Otto, Sherrill Headrick, Otis Armstrong, Vic Washington, Tony Lorrick and Tony Cline.

A Stanford graduate who played three years in the NFL, Stillwell, 35, is disabled by back and knee injuries. He is pursuing a master’s degree in psychology and counseling and wants to work with retired players and others in crisis.

“It seems distasteful to talk about people like me,” he said. “I was part of the football mentality, locked into the feeling I was unbeatable. I was an All-American in college and made the all-rookie team in 1975. I felt invincible. I never worried about losing my ability.

“Now, though, I have lost my athletic ability, my physical condition, my job and I’m going through a divorce. . . . I’ve lost nearly everything that gave me a sense of self-worth. And I know a lot of others who do feel lost.”

Stillwell still has dreams of himself playing football that he says are as vivid as game films. He also dreams about being on the operating table, which he has occupied nine times.

Looking through a scrapbook, or maybe preparing for a test, can trigger that old adrenaline surge so familiar to a player, he said.

“That’s the most painful thing, when I experience the physical power I once had,” he said. “I start to feel like I can overcome this, that I can repair myself, even come back and play. It’s irrational, but I loved the game so much. It’s so painful now when I get physically pumped, because I can’t get up and run anymore.”

He believes there is an unmet need to educate young players about the risks they undertake as players and the rights they have as retirees.

“So many are in need of medical or psychological attention,” he said. “I think it’s an outrage.

“The really scary thing is that nobody knows the ultimate cost of this intense experience of being a football player. When I think about all the injections I had, I’m thankful I never took steroids.

“But I can understand that most guys will do anything to keep their job or get a competitive edge. It’s a horrible thing . . . but you are replaceable. To be successful, you learn to suck it up and play hurt, but it destroys your body and your mind.”

It is hard to measure just how destructive the game is, Yaras said.

There are seven former players, including Stingley, who are receiving total disability benefits of $4,000 a month, plus the other group of seven seeking that benefit.

There may be as many as 100 more whose conditions have degenerated to the point they are unable to work, in the estimation of Yaras and Page. Some in this group may not meet the technical criteria to qualify for a total disability benefit, and others may be too embarrassed to apply.

Page, 41, now a special assistant to the Minnesota attorney general, realized the retirees’ thinking during his years of arguing benefits claims on behalf of the players’ association.

“It’s the nature of the game that you are asked to be part of a team and give 100%,” the former Minnesota Viking defensive lineman said. “Every player gives as much as he can, even when he gets hurt.

“Later, when seeking benefits because of injuries, management often tells those players, ‘No, you are not injured, you didn’t make enough of a contribution.’ That’s a real blow to players so identified with a team to get that kind of rejection, particularly when they have a valid claim.”

The NFL’s pension and benefits plan is one of the most comprehensive of any industry, said Dennis Curran, director of operations for the NFL Management Council.

“Our players have a lot of protections,” he said. “We make sure that if they are injured and unable to play, they get a salary for the remainder of that season and half salary the next year.

“Our retirement plan has several types of benefits. One is a line-of-duty benefit, where an injury caused the player to leave football. It runs five years. If a player then becomes totally and permanently disabled, he can apply for another class of benefits. . . . Our program goes far beyond the protections for most industries.”

As a result of successful investments in the stock market, there is more than $200 million in the players’ pension plan. Yaras said the plan is over-funded, but management contends that valid claims are being paid and if players want to change the criteria, they’ll have to do so in collective bargaining.

But it isn’t realistic, according to Stingley, to think that players will put long-term benefits ahead of free agency, the key to higher salaries.

“When you see players dance and boogaloo in the end zone, you realize they are caught up in their careers and statistics and getting all they can while they can,” Stingley said. “In a way, they’re playing right into the owners’ hands. It’s the older guys who have to fight and scrap for better benefits, but they would all be better off if they could think about the whole picture. Nothing is forever.”

Yaras put the burden on the owners to be more flexible in determining who deserves benefits.

“The bottom line is that we are not paying enough in benefits,” Yaras said. “Management must address the fact that players are not disposable parts and must be responsible for football-related conditions that have degenerated to the point that a man cannot work at any occupation 10 years after leaving the sport.”

The area of conflict often is determining if a player’s disability is strictly football-related. To illustrate how severe the conditions are for certain benefits, a player must lose 50% of the use of his back, or 80% of the use of a knee, according to Page.

“The vast majority of retired players are able to function,” he said. “But still, it is very difficult not to become embittered, because those injuries never go away, never get better.

“I have a little finger that was dislocated and deformed. It doesn’t hurt or limit me, but it is never going to straighten out. If that were a knee, and I was in the position of getting the cold shoulder from management, I’d be pretty upset.”

The problem is not limited to owners wanting to limit contributions to the pension fund, Page said. Active players must share some of the blame, as well.

“Many (active) players are short-sighted,” he said. “They figure they will take care of the future when it gets here. What they forget is that we all get old.”

Otto has been disabused of that illusion.

Doctors have told him he has the body of a 90-year-old man. He would like to be able to swim or play golf but is unable to do so. Because he can’t exercise, he must eat carefully to maintain his weight at 218 pounds, down from 265 as a player.

“I enjoyed what I was doing as a center in the NFL,” he said. “I put my body to the test, used it to the best of my ability, and it wore out.”

He has been seeking increased benefits for total disability for seven years but expresses little bitterness over the delays.

“I never had anything against the owners,” he said. “They have to be skeptical. They argued that my injuries were not football related, these things came after my retirement. . . . The truth is, nobody wants to pay. You gotta prove everything. They won’t just turn the money over.

“I am trying to bring this to the forefront for other athletes. They deserve to be compensated. Some may think they have nothing coming, even while they are getting Social Security disability. After what I have been through, I hope it will help somebody else.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.