SISKEL AND EBERT: WINDY CRITICS

CHICAGO — “Gene! Love the show, but you really do have to lighten up a bit, honey.”

Gene Siskel, co-star of “At the Movies,” the wildly successful syndicated TV movie-review show, was hanging out with wife and friends at Ed Debevic’s, the Windy City’s trendy answer to a retro 1950s hamburger joint.

But Siskel’s adoring public wouldn’t let him alone: They kept coming up to him, wanting to know if “After Hours” was really worth seeing, what he thought of “Krush Groove,” giving him the kind of in-your-face looks that denote celebrity recognition. And now this large, loud-mouthed, gaudily dressed woman was letting Siskel know that he was too uptight for her taste.

“Well,” responded the film critic for the Chicago Tribune, “how about if I do the next show naked?”

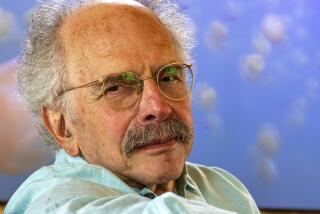

That may be going too far to please a fan. But the lean, balding Siskel, 39, and his hefty adversary across the aisle, Roger Ebert, 43, the Pulitzer Prize-winning critic for the Sun-Times, have not been above making “Saturday Night Live” appearances (reviewing the sketches, awkwardly) and going one-on-one in basketball on “Late Night With David Letterman,” among other blatantly show-biz antics.

Siskel and Ebert have climbed to the top of the heap of TV critics with “At the Movies” and will probably never again be the simple newspaper staffers they once were. The show is seen on 143 stations (including 49 of the top 50 markets and KABC-TV in Los Angeles) by (the claim is) more than 10 million people, giving them perhaps more impact on the box office than any other reviewing entity in the country (see accompanying article assessing their clout) and celebrity status.

Siskel eschews it: “I don’t really think I’m a celebrity. “I’m more of a ‘familiar.’ In Chicago, I’m recognized quite often. Other places, surprisingly often. The most common reaction seems to be, ‘I like the show. . . . What should I go see?’ ”

That, in a nutshell, is what the Siskel-Ebert phenomenon is all about. They have made it big by primarily being A Coupla White Guys Sittin’ Around Talkin’ About Movies--albeit intelligently, with some flair.

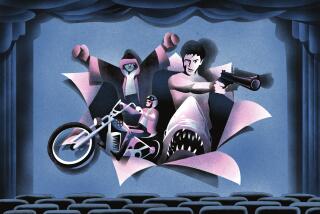

Since 1978, when they debuted on the PBS series “Sneak Previews,” this Frick and Frack and Mutt and Jeff--the “expansive” Ebert and the “imploding” Siskel--have built up a loyal following by giving a “thumbs up” or “thumbs down” to new releases.

Average-looking, even schleppy, boringly normal, they have successfully defied the usual requirement for “star quality.”

“Obviously, we were not cast for our looks,” said Ebert, the jocular raconteur of the duo. “To understand our success, you have to watch ‘This Old House’ on PBS (on which carpenters, etc., show novices how to remodel old houses). It’s somebody who knows what he does, and likes talking about it, two professionals talking about what they’ve done all week. I believe you could put on a show in which two plumbers talk to each other, not in this hideous ‘talkshowese,’ and people would watch it.”

“So much of TV is boring people talking about things they don’t know anything about,” put in Siskel. “Here you have two real people. We don’t look like we should be on TV, we stumble with words, we don’t dress sharp. (But) we’re enormous competitors, and we’re talking about something we love.”

Figures are hard to come by but sources estimate their income in the mid-six figures. They may make as much as $100,000 each from their newspaper jobs, about $125,000 from syndication and more money from local TV gigs (each reviews for Chicago stations), book deals (Ebert has two out in paperback) and other ancillary benefits, such as $10,000 to review concessions for the National Assn. of Concessionaires at its national convention in Las Vegas last year.

It’s almost impossible to see the money. These guys dress Newspaper Preppy, with V-neck sweaters and khaki or corduroy pants. Siskel drives an 11-year-old Pontiac; Ebert owns a small, late-model red BMW, strewn with audio cassettes and foil-wrapped remains of bread loaves past.

The money shows at home. Siskel, his wife and 2-year-old daughter inhabit a 10-room, $500,000 co-op apartment in a restored building in the Chicago Gold Coast neighborhood. Bachelor Ebert lives in a 19th-Century, three-story house near the snappy Lincoln Avenue area--plus a small vacation cabin in Michigan.

If it weren’t for their celebrity, Siskel and Ebert say, they’d still be slogging away on their papers. “I think it’s important to the show that we continue to work for the Sun-Times and Tribune,” Ebert said. “We are professional rivals.”

“I like immediate response,” Siskel added, “which is why I like the newspaper business. The greatest high I get professionally is still from a good article in the newspaper.”

The “At the Movies” set at WGN was quiet on a Thursday afternoon, with a crew of six waiting for the ritual to begin. The set consists of a fake movie balcony and motion picture screen, and nothing else. The script has been formularized to such an extent that it almost seems done by rote. The only addition to the stew, the one that seems to make the show so popular, is the unscripted banter.

Ebert tends toward gregariousness. He’s practically a textbook case of the only-child syndrome, a man who loves being the center of attention. He grew up in Urbana, Ill., majored in journalism at the University of Illinois. At 24, he became the film critic for the Chicago Sun-Times. In 1975, he also became the only newspaper movie critic to ever win a Pulitzer.

He’s the motor-mouthed storyteller who loves to crack jokes and act out the roles of long anecdotes. At the taping, he told a hilariously scatological story in Italian dialect. He provoked an argument with the producer over an arcane production point while nearby, Siskel, the crew and a reporter listened uneasily.

“Roger,” a crew member said, “always has to be right.”

Siskel, youngest of six children, was raised in suburban Glencoe, studied philosophy at Yale and was basically hired at the Tribune to knock Ebert off his perch. The consensus at their respective papers is that Siskel is the better reporter, Ebert the better writer (both tend to agree with that assessment).

They compete intensely. They’ve been known to sneak out of these tapings to set up secret interviews.

Last year, Ebert had lined up a Woody Allen interview for “The Purple Rose of Cairo.” Siskel wasn’t interested in Allen--whom he felt was overexposed--but he had scheduled a rare interview with Mia Farrow. While the two were in makeup for “Saturday Night Live” (they’ve made three appearances), Siskel suggested that he was also going to interview Allen, to throw Ebert off the Farrow trail.

“I had no intention of interviewing Woody Allen,” Siskel explained the other day. “But I said I was going to to upset Roger and so he wouldn’t go after Mia. I have the ability to look this guy straight in the eye and lie to him and he can’t tell.”

Said Ebert: “We’re always trying to get a story that the other doesn’t have. In general, Gene is more into that than I am. He will run a story artificially early in order to get it in before me.”

Ebert has called Siskel the “world’s baldest film critic.” Siskel tried to convince Calendar that the rotund Ebert “is not allowed to wear brown sweaters because he’d look like a mud slide.” But the gibes are all in jest; the two don’t socialize, but there’s mutual respect.

“I like Gene, but we don’t hang out. I hang out with people who are more bohemian and artsy,” Ebert said. “But having been thrown together over the last decade, I’ve found that Gene’s honest and ethical.”

Said Siskel: “I like him, but the nature of our relationship is not ‘like,’ it’s intense journalistic competition. If we were at a party with industry people, Roger would probably be regaling them with stories and I would be hustling interviews.”

When WTTW-TV asked the two to do a review show, they saw the mano a mano concept as a challenge--and as an opportunity to expand their bases.

It was a local monthly show for a while, then regional. Two years later, it went to PBS. The show kept building momentum during its three-year run. But in 1982, after a contract dispute, the critics left for the more insecure world of syndication.

They moved cross town to WGN and signed a four-year contract for double their PBS take of $68,000 per year. Based on a coin toss, they also agreed that Siskel would get top billing for the first two years of the contract, Ebert for the next two.

They’ve become the most visible stars of the crit scene--and most sought after. They are courted assiduously by studios, ad agencies, film festivals, trade conventions, even rib-tasting contests.

They maintain a strict “no commercials” policy and have done a thumbs-down on offers from Miller Lite, United Airlines and an unnamed company that, Siskel said, offered them “a $50,000 guarantee plus more money down the line.” Because of their punishing schedules, they’re careful about speaking engagements, film festival appearances, interview requests and screenings. (They passed on the opportunity to review a film about dentistry for a dental conference.)

Both reportedly remain loyal to their papers. Siskel is known to flirt dangerously with deadlines and has been taken to task on accuracy. At one point, the Chicago Reader ran a semi-regular “SiskelWatch” column by Neil Tesser charting Siskel’s alleged errors, which has caused the critic unconcealed fits. (He wasn’t too happy either that Tesser was authoring the accompanying commentary).

“SiskelWatch” has been discontinued but Gary Dretzka, assistant editor at the Tribune, said, “I’m concerned that anyone can do three jobs and go on the lecture circuit and remain healthy. Coming from the news side (as Dretzka does), the fear always is, when you’re doing that much work, eventually you’re going to make a monumental mistake.”

But Siskel “still burns for newspapers,” according to Bob Carr, arts editor of the Tribune. “He still turns out as much copy as anybody on the newspaper staff. Every time he beats Roger (on a story), he revels in it. He’ll say, ‘Take that, Tubby, I got him again.’ He loves it.”

Across the street at the Sun-Times, features editor Carroll Stoner said: “Roger has a reputation as a skilled journalist and as a nice person. He is a stimulation freak. He likes having people around.”

Once an ambitious screenwriter, Ebert has had to worry about conflict-of-interest: Under the pseudonym R. Hyde, he wrote screenplays for “Beyond the Valley of the Dolls” and “Beneath the Valley of the Ultravixens” made by sexploitation maker Russ Meyer, but never reviewed a Meyer film once they were associated. He also wrote an unproduced screenplay for director Sidney Furie, but said that he did not review any of Furie’s films during their association.

“I think at that time,” Ebert said, “I had the dream of being a screenplay writer, but I don’t have that ambition anymore. It’s a conflict of interest. When you’re a film critic, you have to stay away from that.”

Their fans seem to deliver unto them the adoration usually reserved for rock and movie stars. For example, take the enormous black man who approached Ebert one day while he was having breakfast at a neighborhood coffee shop.

“Hey, man, you see ‘Krush Groove?’ ”

“Yes,” Ebert answered, “and I wasn’t too crazy about it.”

“Gee,” said the fan, “I’m a bodyguard, and I was a bodyguard for some of those acts (in the film) when they were in town, and I was just wondering if I should catch the film.”

“Well, all I can say is, I didn’t think too much of it.”

“OK, thanks,” said the fan, who then went to the takeout counter to get some coffee. Before he left, he was back at Ebert’s table.

“Listen, man,” he said, handing Ebert a business card, “if you ever need a bodyguard at any time, just give me a call, you hear?”

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.