City of Glass by Paul Auster (Sun & Moon: $13.95; 203 pp.)

“I have come to New York because it is the most forlorn of places, the most abject. The brokenness is everywhere, the disarray is universal. You have only to open your eyes to see it. The broken people, the broken things, the broken thoughts. The whole city is a junk heap. It suits my purpose admirably. I find the streets an endless source of material, an inexhaustible storehouse of shattered things. Each day I go out with my bag and collect objects that seem worthy of investigation. My samples now number in the hundreds--from the chipped to the smashed, from the dented to the squashed, from the pulverized to the putrid.”

“City of Glass” is the first in a New York trilogy, an experimental novel that wanders and digresses and loses its own narrative thread, but with all that, keeps offering bits of dialogue or scenes or “ideas” that make the whole thing much like a very good day for a street scavenger: In among the nondescript junk, there are maybe a hundred little treasures. . . .

“City of Glass” is about the degeneration of language, the shiftings of identity, the struggle to remain human in a great metropolis, when the city itself is cranking on its own falling-apart mechanical life that completely overrides any and every individual. Our hero, our narrator, has already gone through several lives, several identities. His name, he tells us, is Quinn (which rhymes with twin and bin ). For a while he was “William Wilson,” but before that “he had published several books of poetry, had written plays, critical essays, and worked on a number of long translations. . . .”

But quite abruptly, he has changed all that. As Wilson, he took a pseudonym within a pseudonym, and began to write a series of detective novels about a private eye named Max Work: “In the triad of selves that Quinn had become, Wilson served as a kind of ventriloquist, Quinn himself was the dummy, and Work was the animated voice that gave purpose to the enterprise.”

Once all this has been established, we are instructed to see Quinn as bereft of a wife and child, a “bachelor” living alone, interested in the fate of the Mets, one of those sad, single guys who eat breakfast alone at lunch counters. The author then allows him to get a phone call (put through by mistake?) asking for Paul Auster (the author of this book). This is a plea for some detective work and Quinn/twin, after hesitating, answers that request.

A loving wife has a crazy husband, who has been locked up in a dark room for the first nine years of his life by a mad dad, who sometimes takes the name of “Henry Dark” to use as a mouthpiece for some of his more revolutionary scholarly ideas about language, civilization, Paradise and child-rearing. This mad dad, whose name is Stillman, has been put in jail some years before for abusing his son, and is just now returning to New York. Quinn/Auster, because of his stories about Max Work, and because he has nothing else to do, agrees to watch for theelder Mr. Stillman.

Except, of course, when Mr. Stillman gets off the train at Grand Central, there are two of him--one shabby, one perfectly dressed. Quinn makes an arbitrary decision and begins to shadow the shabby one, starting a long journey through the city to his ultimate destiny.

Walking through the city! This really is a New York novel. Quinn walks the length and breadth of Manhattan Island just for the heck of it, and the elder Mr. Stillman, in his walks, manages literally to spell out cryptic messages about the meaning of life. It is Stillman who sees the great Metropolis as a city “of broken people, broken things, broken thoughts,” but that falls right in with his theory that we are to return soon to a “prelapsarian” condition; a universal language, a universal state of well-being. Of course, Stillman has cracked completely, as Quinn realizes, as he presents himself to him in a series of interlocking identities.

Quinn, at one point, begins to wonder about the “real” Paul Auster and goes to see him --and if you’re thinking that Pirandello and Unamuno and a hundred other serious writers and tens of thousands of undergraduates have pondered the relationship between character and author, it really is OK, since those “identities” are only two among 20 or so.

In fact, Auster’s laconic, throw-away, often very funny tone keeps this book (and many of its ideas) fresh. If, during the middle of the narrative, the reader entertains a few vagrant thoughts about where this novel is going, what Quinn/Wilson/Work/Auster is up to anyway, that question is satisfactorily answered in a series of ending scenes that mustn’t be given away--except that there’s a clue hidden in this sentence.

It’s true, in a small town we are born, live and die as more or less one person, because that’s the way our family and friends know us. In cities, we either rush to change our identities--or they are changed brutally for us. “City of Glass” thoughtfully and cleverly draws our attention to these questions of self.

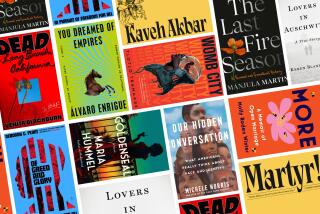

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.